Introduction to Large Language Models

and Retrieval Augmented Generation

Introduction to Large Language Models

and Retrieval Augmented Generation

and Retrieval Augmented Generation

John McNally

Principal Academic Solutions Developer

Wolfram Research

Wolfram Research

Syllabus

Syllabus

Key questions

Key questions

What is...

◆

a large language model?

◆

an embedding vector in latent space?

◆

retrieval augmented generation?

◆

a vector database?

Key skills

Key skills

In this segment, you will see how you can...

◆

prompt large language models

◆

create a semantic search index

◆

create a simple AI agent

◆

work with neural nets in Wolfram Language and Mathematica

Language Models

Language Models

A language model is simply a specific kind of artificial neural network. The most successful language models are currently based on a transformer architecture. It should be noted that transformers are not the only possible architecture and Mamba models for sequence learning are another notable option.

Working with Neural Nets

Working with Neural Nets

OpenAI is releasing previews of GPT-4.5 these days, and you will see how to connect to this service later.

First, let’s first retrieve the open-source GPT-2 language model from the Wolfram Neural Net Repository:

languagemodel=NetModel["GPT2 Transformer Trained on WebText Data","Task"->"LanguageModeling"]

Out[]=

NetChain

What does this neural net output?

languagemodel["hello world"]

Out[]=

.

Given some text, often called a prompt, the language model predicts the next bit of text.

Each bit of text in the vocabulary is called a token.

It turns out that the inability of early language models to do mathematics had a lot to do with suboptimal choices for how to tokenize text. This part of the course won’t go into details, but know that this step is actually non-trivial and has also come a long way since GPT-2:

languagemodel["2 + 2 ="]

Out[]=

3

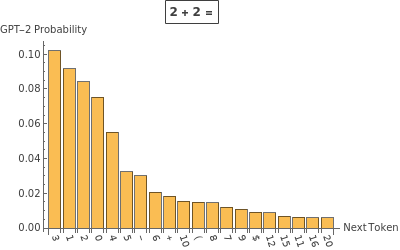

Let’s look at the probability for multiple continuations:

Out[]=

Prompt engineering is the task of crafting prompts that nudge probabilities in a favorable direction for the behavior you want to see. Note that each generation of language models (and even each individual model) will have slightly different best practices for prompting.

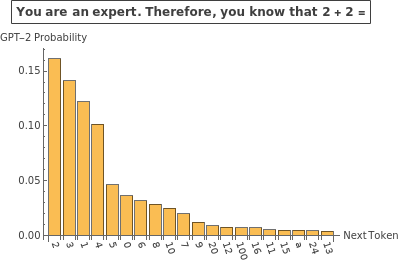

Even this very old model nearly doubles its probability assignment for the desired response when told to play the role of an expert:

With[{p1=languagemodel["You are an expert. Therefore, you know that 2 + 2 =",{"Probability"," 4"}],p2=languagemodel["2 + 2 =",{"Probability"," 4"}]},p1/p2]

Out[]=

1.84808

To speak very loosely, the additional context puts the language model in a very different “head space” for predicting next tokens:

Out[]=

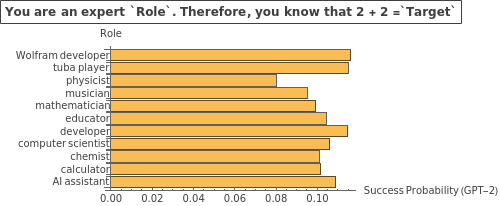

Let’s run a quick experiment to see how some text giving this model a role affects the probability assigned to the desired token. The results are amusing:

Out[]=

Keep in mind, this role-based prompt engineering is not always helpful as argued by Zheng et al (2024). However, this topic is still the subject of ongoing research such as Poterti et al (2025).

Sampling and Temperature

Sampling and Temperature

In order to compute probabilities, the final layer of a language model will apply what is called a softmax layer by ML people. You might know this as a Boltzmann (Gibbs) distribution.

Information[languagemodel,"SummaryGraphic"]

Out[]=

The outputs of the classification layer are the analog of the (negative) energies from statistical mechanics, and they are called logits in this context.

Out[]=

Your Turn

Your Turn

Look at the model’s structure to find the name of the layer preceding the SoftmaxLayer named “probabilities”:

languagemodel

Out[]=

NetChain

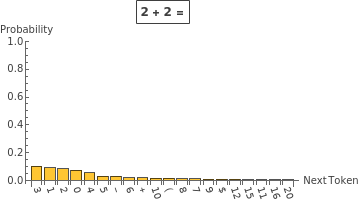

Compute the logits for possible continuations of “2 + 2 =”:

Plot the result for the 10 “lowest energy” continuations:

Transformer Architecture and Attention

Transformer Architecture and Attention

You now know what a language model does, but how does one work?

The process is operationally a bit complicated but conceptually simple as seen in this summary graphic:

If you zoom in on the “embedding” block, notice that a raw token-level embedding is combined with a positional embedding. A transformer does not inherently take into account the order of input sequences, and so this positional embedding is needed for successfully learning language:

If you zoom in on the “decoder” block, there are multiple “attention blocks” inside. This is a graphic of one of them:

Each attention block has multiple attention heads to “pay attention” to different parts of the data. The graphic below shows the weights for this four-token input:

The above matrices being lower triangular are a consequence of using causal attention: the model can’t “cheat” by reading the end of a string before it is generated. Enforcing the causality constraint is relevant for text prediction but can have disadvantages for other applications.

Vector Databases

Vector Databases

A vector database is commonly used as a tool to give language models additional information that they wouldn’t know out-of-the-box. Vector databases allow search by semantic content, not just keywords.

Embeddings of Text

Embeddings of Text

In the graphical representation of GPT-2, notice that right before the classification layer, there is a 768-dimensional vector produced by the model:

In other words, the thing being classified to determine what should come next is an embedding vector in a latent space, not the text directly. This is a standard technique in language models and many kinds of classification tasks.

This model now maps strings to vectors. In the latent space, it is most common to use cosine distance as the relevant metric (as most embedding models also normalize their outputs).

You can compute the pairwise distance between embeddings in the latent space:

You can get some sense of the topology of the embedding into the latent space space with plots like these:

One of the reasons why GPT-2 is less proficient than its newer cousins is because the embeddings it produces don’t map as cleanly onto our human intuitions of related concepts.

Compare to a different embedding model, BERT:

This embedding model maps a bit better onto human intuitions:

A “better” embedding model, SentenceBERT, maps onto human intuition for analogies even more cleanly:

The (dimension-reduced) embeddings using this older model don’t give a particularly useful structure for analogy reasoning:

However, using a better embedding model (and appropriate dimension reduction) lets you “see” an analogy as mapped into the latent space:

Semantic Search

Semantic Search

To use a vector database, the system will embed a query string, then return items whose embedding vectors are nearby the query vector.

Keep in mind this only works if the database strings and query string are embedded into a latent space using the same mapping (i.e., the same embedding model).

Here is an example search index of resource functions in our repository:

The following snippets of documentation are “close” to the user’s query in embedding space:

Retrieval Augmented Generation

Retrieval Augmented Generation

The phenomenon of LLM hallucination occurs because language models will always say something, even if they don’t really have the appropriate context on which to generate appropriate text:

Notice that the new model does helpfully link a web address to verify its claim. However, following that link reveals that the LLM response below is no longer up to date:

Creating a Semantic Search Index

Creating a Semantic Search Index

To automatically create a vector database associated with a source (in this case a wiki) you can use the CreateSemanticSearchIndex function:

While you could create an LLMTool which the model would use, you can use an LLMPromptGenerator to programmatically add context:

With a search of the index you have provided automatically conducted, the model will now answer according to the new information it was given:

Note how the prompt and query that are used by default return the relevant information as the 5th context item in this case:

This is because the search index and query were generated in the simplest automated way. If you provide a better search query to the index, you get the desired result as the first item returned:

Another best practice is to think more carefully about what you want to embed and then associate a payload to return for that query.

Adding Annotations to a Semantic Search Index

Adding Annotations to a Semantic Search Index

With some string parsing, create an annotated list of sources and an annotated index:

Define a helper function to visualize the results:

Now, the most concise key phrase matches exceptionally well with the section heading that contains the desired info. The payload delivered to the model can be the text from that section:

Using the user’s raw input still returns the desired section with highest relevance; however, the extraneous wording in the user’s raw input lowers the relevance score.

To improve the search phrase used, you can use an LLM to summarize the user question into a search phrase:

This can be combined into a more sophisticated generator of prompts:

You can hover over the tooltip to see what prompt was generated with this more sophisticated set-up: