In this computational essay, I explain and demonstrate attacks on facial recognition and face detection algorithms. The goal was to inform general audiences of the history of these techniques, and to use knowledge of their inner workings to craft effective mitigating algorithms.

In our connected society, being in public life necessarily means being subjected to the gaze of cameras. Their surveillance never stops, they have a memory that can be practically limitless, and often you’re in the sights of more than one. Living in the 21st century means that some of the cameras we see daily aren’t just a method of recording and replaying past events, but an active surveyor that can match your face to your identity and use that knowledge in computations you didn’t consent to. Why should simply existing in public spaces imply your consent to being computed on? Why should we be subjected to such treatment when we cannot know if the ontology the computer system uses accurately represents us? This motivates further understanding of facial recognition systems aimed towards a general audience, in service of a well-informed public opinion on privacy in a politically turbulent period.

Facial Recognition & Facial Detection

Facial Recognition & Facial Detection

Facial recognition and facial detection are two similar, but critically different kinds of systems that are very commonly conflated. Facial detection is a set of algorithms that identify if faces are present in an image or frame of video (commonly marking their location in the image), whereas facial recognition is a set of algorithms that not only identifies faces, but also matches any identified faces to an identity. How this is achieved varies from algorithm-to-algorithm.

Early methods of facial recognition relied primarily on manually-placed facial landmarks—the distance between your eyes, for example. Smarter methods eventually came around, like the application of Principal Component Analysis to facial recognition. This method generates wonderfully creepy eigenfaces, which can be recomposed with linear operations (scaling and adding brightness levels, effectively) to represent the faces that existed within a training sample of face images.

Below are some eigenfaces from the AT&T ORL Database that were added to the Wikimedia collections. A face broken up into its respective eigenfaces is like a signature, and can be matched with images of faces that are made up with similar eigenfaces.

Early methods of facial recognition relied primarily on manually-placed facial landmarks—the distance between your eyes, for example. Smarter methods eventually came around, like the application of Principal Component Analysis to facial recognition. This method generates wonderfully creepy eigenfaces, which can be recomposed with linear operations (scaling and adding brightness levels, effectively) to represent the faces that existed within a training sample of face images.

Below are some eigenfaces from the AT&T ORL Database that were added to the Wikimedia collections.

1

Out[]=

Today’s methods are, in fact, somewhat similar to these eigenfaces. Let’s take a look at a somewhat new model from CMU’s Mahadev Satya.

2

In[]:=

openFace=NetModel["OpenFace Face Recognition Net Trained on CASIA-WebFace and FaceScrub Data"]

Out[]=

NetChain

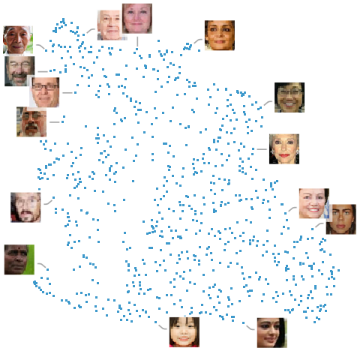

Like these classical methods, we’re doing quite a bit of linear algebra. Unlike classical methods, this linear algebra is a neural network which has learned to cluster similar faces in similar places inside a 128-dimensional feature vector. The idea of a feature vector may be unintuitive if you haven’t encountered it before, but it can be thought of as a way of compressing complex ideas (like pictures) into a collection of numbers that holds important information. A single number in a feature vector might be the breadth of the nose, for example; though, oftentimes the meaning of a single number is much more strange and opaque than this example (this is just the nature of things created by neural networks—they don’t always make sense to humans). Unsupervised neural networks, like OpenFace, learn to create these feature vectors without human oversight. Below is a plot of this 128-dimensional space, reduced into 2D for your viewing pleasure.

In[]:=

facesDataset=;allFaceImgs=;

Out[]=

If you have Wolfram or Mathematica, I recommend running the code above on your own machine so you can hover over data-points and see the associated image. You can see a handful of clusters (e.g. the older people in the dataset seem to be concentrated in the top-left and the younger people seem to be concentrated in the bottom-middle), but generally speaking individual numbers that make up a feature vector don’t correspond to human notions like age, but more weird things like the color of the shadow cast on the philtrum by the nose.

By taking two faces, converting them into feature vectors with models like OpenFace, and then taking the difference of the angles of the vectors (using CosineDistance, for example), we can calculate how different two images are. If the difference is below a certain threshold, denoted ϵ, we can consider the two faces to be the same person.

By taking two faces, converting them into feature vectors with models like OpenFace, and then taking the difference of the angles of the vectors (using CosineDistance, for example), we can calculate how different two images are. If the difference is below a certain threshold, denoted ϵ, we can consider the two faces to be the same person.

Potential Vulnerabilities

Potential Vulnerabilities

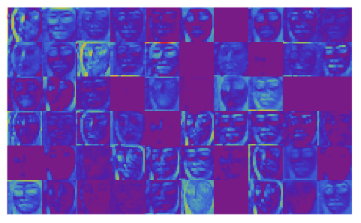

We’ve covered what makes facial recognition work, but what makes it stop working? By looking at the activations inside OpenFace, we can see what it finds important to the structure of faces.

Out[]=

Naturally, most of the information stored is located in the contours. Some of these squares (called channels) show activations located around the eyes, others show activations around the nose and philtrum, and still others show activations around the jawline. Often these channels focus on a combination of features. These channels are essentially a heat-map of places where we can disrupt the recognition process by placing objects.

Fooling Facial Recognition Systems

Fooling Facial Recognition Systems

Occlusion

Occlusion

Occlusion is the easiest, most accessible, and most practical attack on facial recognition—so simple you might not even consider it an attack! If a facial recognition system can’t see important details of your face, it cannot identify you. For example, consider the simple balaclava:

In[]:=

unmasked=

;masked=

;CosineDistance@@(openFace[#]&/@{masked,unmasked})

Out[]=

0.333485

This image from Wikimedia depicts a man wearing a balaclava in a few different ways. When we crop out one section where he’s unmasked and another section where he’s wearing the balaclava completely, run the two through the embedding model (flipping one and cropping ensures the model isn’t sneakily getting extra identity information from the orientation of the face and background—which it shouldn’t be considering if we’re only considering the morphological components of the face) and take the cosine distance between the two results, we get a cosine distance of 0.33, which is a little bit more than the cosine distance of the same person in two different lighting environments.

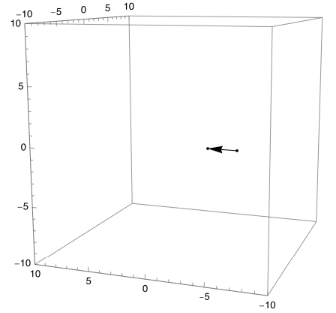

We can actually visualize this change using plots. This plot below shows the change in the embedding vector from the man not wearing the balaclava to him wearing the balaclava.

3

We can actually visualize this change using plots. This plot below shows the change in the embedding vector from the man not wearing the balaclava to him wearing the balaclava.

Out[]=

CV Dazzle

CV Dazzle

CV Dazzle is the first of our more suave, 007-style attacks. Designed by the artist and researcher Adam Harvey for his 2010 Master’s thesis, CV Dazzle is a type of attack on face detection first implemented against the Viola-Jones Haarcascade algorithm. Please note that CV Dazzle is an attack on face detection rather than recognition (something to keep in mind for when we compare and contrast these attacks at the end of the section).

Let’s see how CV Dazzle works against the algorithm it was designed to protect against, which happens to be implemented in Wolfram Language as a Method option.

4

Let’s see how CV Dazzle works against the algorithm it was designed to protect against, which happens to be implemented in Wolfram Language as a Method option.

Define a list dazzle that contains images of CV Dazzle makeup.

Create a row of graphics where the CV Dazzle looks are highlighted with boxes where the HarrCascade algorithm believes there are faces.

Create a row of graphics where the CV Dazzle looks are highlighted with boxes where the HarrCascade algorithm believes there are faces.

In[]:=

dazzle=;GraphicsRow[(HighlightImage[#,FindFaces[#,Method->"HaarCascade"]]&/@dazzle),ImageSize->Full]

Out[]=

Interesting—it seems like the first look completely fooled Haarcascade; the rest have mixed success. The second look is completely see-through, but the third and forth looks (both photographed at slightly grazing angles) smoosh the bounding boxes around in strange ways. I imagine this squishing effect would be more significant if these images were photographed in less professional lighting, and from angles that a typical security camera might be viewing someone.

Now that we know Haarcascade is somewhat fooled, let’s see the results when we allow the function to automatically pick out a detection method by omitting the Method option.

Now that we know Haarcascade is somewhat fooled, let’s see the results when we allow the function to automatically pick out a detection method by omitting the Method option.

Create a row of graphics where the CV dazzle looks are highlighted with boxes where a face detection algorithm believes there are faces.

In[]:=

GraphicsRow[(HighlightImage[#,FindFaces[#]]&/@dazzle),ImageSize->Full]

Out[]=

It seems FindFaces can easily identify these faces, likely with convolutional methods. Let’s try to create our own CV dazzle look that can fool FindFaces, regardless of what method it uses.

In[]:=

nFaces[num_Integer]:=RandomSample[allFaceImgs,num]

Define a method faceObscureRandom that takes in a face and randomly places a colorful rectangle over it.

In[]:=

faceObscureRandom[im_Image]:=Module[{i=RandomReal[1],j=RandomReal[1],k=RandomReal[1],l=RandomReal[1],x=RandomInteger[200],y=RandomInteger[200]},rect=Graphics[{RandomColor[],Rectangle[{i,j},{k,l}]}];{ImageCompose[im,rect,{x,y}],{{i,j},{k,l},{x,y}}}]

In[]:=

coveredRandom:=Transpose[faceObscureRandom/@nFaces[5]][[1]];GraphicsRow[HighlightImage[#,FindFaces[#]]&/@coveredRandom,ImageSize->Full]

Just randomly placing a rectangle over the face works sometimes, but it’s both inconsistent and a bit of a cheat—we’re effectively back to just occluding the face. If we make the disruptions randomly cover parts of the face with less opacity, it’s a little more similar to actual CV Dazzle.

Define a method faceObscureFeatures that takes in a face, acquires random points located on facial landmarks, and draws a number of slightly transparent lines between those points on the face.

It’s still a little clunky, and certainly not an excellent approximation of makeup, but it’s a little more faithful. After running this code a handful of times over, looking at which outputs block FindFaces, it seems that the most effective places to place makeup when attempting CV Dazzle are the nose and jawline; specifically, these regions should be covered in a very dark pigment to ensure there is no visible contour.

Poisoning Attacks & Nightshade

Poisoning Attacks & Nightshade

Comparing Attacks

Comparing Attacks

Conclusion

Conclusion

In this essay, I hope to have informed you of the history of facial recognition, explained the difference between it and face detection, and motivated you to be more wary of the facial recognition technology that appears in our everyday lives. These systems, while they may be technologically impressive, are far from infallible. Vulnerabilities span from simple methods like occlusion, to sophisticated forms of resistance like CV Dazzle, and to modern data poisoning attacks such as Nightshade. These techniques are not just technical curiosities, but critical tools that should be exercised liberally in a world where we are so infrequently asked for consent before being attached to an identity.

Extensions and Further Goals

Extensions and Further Goals

An important, but untouched subject in this essay is the minimal face coverage needed to reliably evade facial recognition. Minimizing this isn’t immediately intuitive, as facial recognition models aren’t a continuous function. It isn’t exactly clear how one might optimize over a space of images either. This kind of optimization problem might be another good application for machine learning, but I think simulated annealing might produce better results. Futhermore, the dataset of face images that this essay uses consists entirely of clear, 200-by-200 pixel images of people with their faces cropped and in focus. A dataset of in-the-wild, blurry, greyscale images would be a much more representative of active surveillance tactics, and would allow the efficacy of these tactics to be quantified with higher reliability.

Bibliography

Bibliography