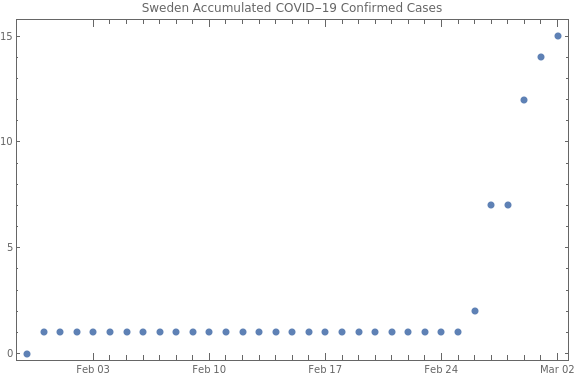

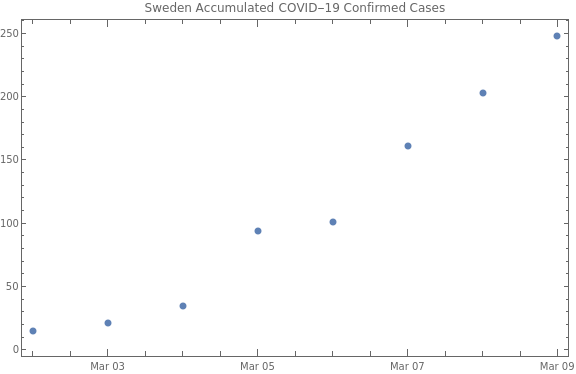

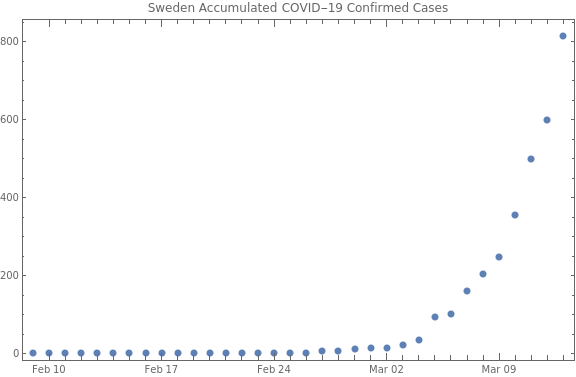

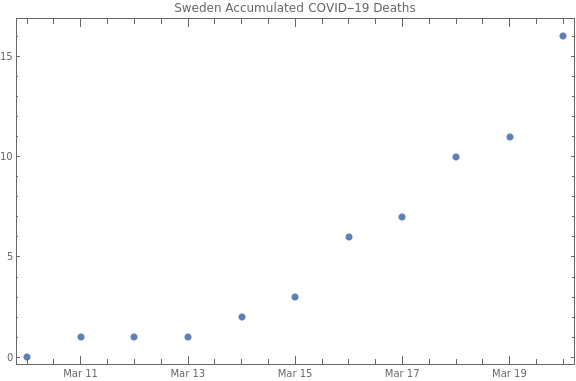

rawCovidData=ResourceData["Epidemic Data for Novel Coronavirus COVID-19"];confirmedCases=Normal[rawCovidData[GroupBy["Country"],Total,"ConfirmedCases"]];confirmedDeaths=Normal[rawCovidData[GroupBy["Country"],Total,"Deaths"]];confirmedCasesSweden=TimeSeriesWindow[confirmedCases[[Key[CountryData["Sweden"]]]],{{2020,1,30},{2021,1,28}}];confirmedDeathsSweden=TimeSeriesWindow[confirmedDeaths[[Key[CountryData["Sweden"]]]],{{2020,1,30},{2021,1,28}}];