A Formula for Primes in Arithmetic Progressions

A Formula for Primes in Arithmetic Progressions

Let and be integers with . If and are relatively prime, then the arithmetic progression where contains an infinite number of primes. The number of such primes that are less than or equal to is a function of usually denoted by (x).

q

a

q>0

q

a

qn+a

n=0,1,2,3,…

x

x

π

q,a

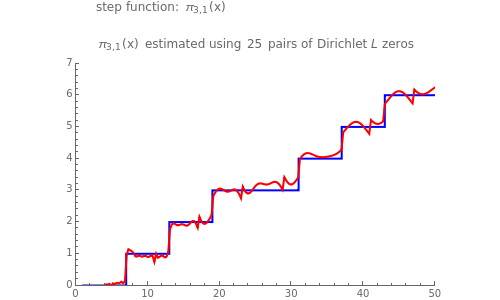

The graph of (x) is an irregular step function that jumps by 1 for every such that is prime.

π

q,a

x

x=qn+a

This Demonstration illustrates the remarkable fact that we can replicate the jumps of this step function by using a sum that involves zeros of Dirichlet -functions. This means that those zeros somehow carry information about which numbers in the progression are prime.

L

Details

Details

Snapshot 1: primes of the form ; the graphs of the step function (x) and the formula using no zeros

3n+1

π

3,1

L

Snapshot 2: the graphs of (x) and the formula using 50 pairs of zeros

π

3,1

L

Snapshot 3: primes of the form ; the graphs of (x) and the formula using 50 pairs of zeros; the step function jumps up at primes 11, 31, 41, 61, 71, …

10n+1

π

10,1

L

Let and be integers with , and with and relatively prime. Dirichlet's theorem (see [3]) says that the arithmetic progression is prime for infinitely many values of . For example, when and , the progression has infinitely many primes, the first five of which are 11, 31, 41, 61, and 71.

q

a

q>0

q

a

qn+a

n

q=10

a=1

10n+1

The standard notation for the number of primes less than or equal to is . Likewise, the number of primes in the progression that are less than or equal to is usually denoted by (x). We will also use Euler's phi (or "totient") function, , which is the number of integers between 1 and relatively prime to .

x

π(x)

qn+a

x

π

q,a

ϕ(q)

q

q

Technical Details:

These equations come from equations (6)–(8) in reference [1]. There is a lot of terminology here. For an introduction to characters and Dirichlet -functions, see reference [3].

L

You use the slider to specify , the number of pairs of complex zeros of Dirichlet -functions to include in the sums. This Demonstration then applies the following formulas to compute (x):

N

L

π

q,a

(1) (x)=+e(x,q,a),

π

q,a

π(x)

ϕ(q)

x

ϕ(q)log(x)

where

(2) ,

e(x,q,a)=-c(q,a)-e(x,χ)

∑

χ≠

χ

0

*

χ(a)

(3) ,

e(x,χ)=

2N

∑

k=1

ρ

k

x

1/2+

ρ

k

and

(4)

c(q,a)=-1+numberofsquarerootsthatahas,(modq)

In equation (1), the largest term is . The other term on the right depends on zeros of -functions.

π(x)/ϕ(q)

L

In equation (2), the asterisk denotes the complex conjugate, and we sum over all characters (mod ) except the "principal" character, .

χ

q

χ

0

In equation (3), for the character (mod ), we sum over complex zeros of the corresponding Dirichlet -function. The sum extends over the zeros having the smallest positive imaginary part, and the zeros having the least-negative imaginary part. (These pairs of zeros are not necessarily conjugates of each other.) denotes the imaginary part of the zero. For speed, this Demonstration uses precomputed zeros of -functions mod 3, 4, and 10.

χ

q

2N

L

N

N

ρ

k

th

k

L

In equation (4), if has no square roots mod (that is, is a quadratic nonresidue mod ), then . Otherwise, must have at least two square roots mod ; this makes .

a

q

a

q

c(q,a)=-1

a

q

c(q,a)≥1

When equation (1) is graphed, we must account for the fact that, for example, neither of the two progressions mod 3 ( and ) include the prime 3. We do this by subtracting 1/2 from each value obtained in equation (1). The same adjustment is made for mod 4, whose progressions omit the prime 2. The mod 10 progressions omit two primes (namely, 2 and 5), so for , , , and , we subtract 1/4, 0, 3/4, and 1, respectively.

3n+1

3n+2

10n+1

10n+3

10n+7

10n+9

Discussion:

Each of the values of that have no factor in common with gives rise to an arithmetic progression that contains infinitely many primes. As approaches infinity, each of these progressions will have the same proportion of primes less than or equal to . There are primes less than or equal to , so each of the progressions has, as approaches infinity, about primes. This explains the first term on the right side of equation (1).

ϕ(q)

a

q

qn+a

x

x

π(x)

x

ϕ(q)

x

π(x)/ϕ(q)

For example, for = 10, each of the = 4 progressions , , , and has about primes, for large .

q

ϕ(10)

10n+1

10n+3

10n+7

10n+9

π(x)/4

x

Notice that equation (1) uses . It might seem like cheating to call something a "formula for primes" when that formula contains . However, can itself be computed by using a sum of terms that involve zeros of the Riemann zeta function. The Demonstration "How the Zeros of the Zeta Function Predict the Distribution of Primes" shows how to do that.

π(x)

π(x)

π(x)

Prime Number Races:

As approaches infinity, each of the progressions will have the same proportion of primes (namely, ). However, this does not mean that the progressions have the same number of primes up to any given . Perhaps the most dramatic example of this happens with . The progressions and each contain infinitely many primes. The first two primes in these progressions are 2 and 5, both of which belong to the progression . The next prime is 7, in the progression . So, these progressions start out with having more primes than . Using the (x) notation, it has been shown that, at least up to , (x)>(x). But here is the amazing part: (x)>(x) for every less than 608,981,813,029! At = 608,981,813,029, (x) finally exceeds (x)! In fact, (608981813029)=11669295396 and (608981813029)=11669295395.

x

ϕ(q)

qn+a

1/ϕ(q)

x

q=3

3n+1

3n+2

3n+2

3n+1

3n+2

3n+1

π

q,a

x=10

π

3,2

π

3,1

π

3,2

π

3,1

x

x

π

3,1

π

3,2

π

3,1

π

3,2

With the two progressions mod 4, namely, and , something similar happens: (x)>(x) for every < 26,861. Then, at = 26,861, (x) finally becomes greater than (x).

4n+1

4n+3

π

4,3

π

4,1

x

x

π

4,1

π

4,3

For : 3 is prime, so starts out in the lead over the other three progressions , , and . (x) first takes the lead over the other three progressions at . (x) first takes the lead at = 72,269. Finally, (x) first takes the lead over the other three progressions at = 45,845,791.

q=10

10n+3

10n+1

10n+7

10n+9

π

10,7

x=157

π

10,9

x

π

10,1

x

Because each progression mod has the same proportion of primes, one might expect that the lead would have switched back and forth much more often, as if one were flipping a coin and tallying heads versus tails. It is surprising that one progression so consistently maintains the lead over the others.

q

For a given , why do some progressions have more primes than others? The key is equation (4) above. If has no square roots mod (for example, has no square roots mod 3), then . If has, say, two square roots mod (for example, has two square roots mod 3), then . But if , then, by equation (2), is larger (by 2) than it would be if , all other things being equal. This, in turn, makes (x) larger when than it would be if .

q

a

q

a=2

c(q,a)=-1

a

q

a=1

c(q,a)=1

c(q,a)=-1

e(x,q,a)

c(q,a)=1

π

q,a

c(q,a)=-1

c(q,a)=1

What this means is that, for values of that have no square roots mod , the arithmetic progression tends to have a few more primes up to a given than other progressions where does have square roots mod . (Of course, will not have enough primes to affect the proportion, which, as approaches infinity, is for every progression mod .) Finally, it is worth noting that in 1914, Littlewood proved (see reference [2]) that, for both mod 3 and mod 4, the lead switches back and forth infinitely many times.

a

q

qn+a

x

qn+b

b

q

qn+a

x

π(x)

ϕ(q)

q

There are many articles about these "prime number races"; for example, [2] is a readable introduction to the subject.

References

References

[2] A. Granville and G. Martin, "Prime Number Races," American Mathematical Monthly, 113(1), 2006 pp. 1–33.

[3] W. J. LeVeque, Topics in Number Theory, vol. 2, Reading, MA: Addison–Wesley, 1961 pp. 81–124.

External Links

External Links

Permanent Citation

Permanent Citation

Robert Baillie

"A Formula for Primes in Arithmetic Progressions" from the Wolfram Demonstrations Project http://demonstrations.wolfram.com/AFormulaForPrimesInArithmeticProgressions/

Published: March 7, 2011